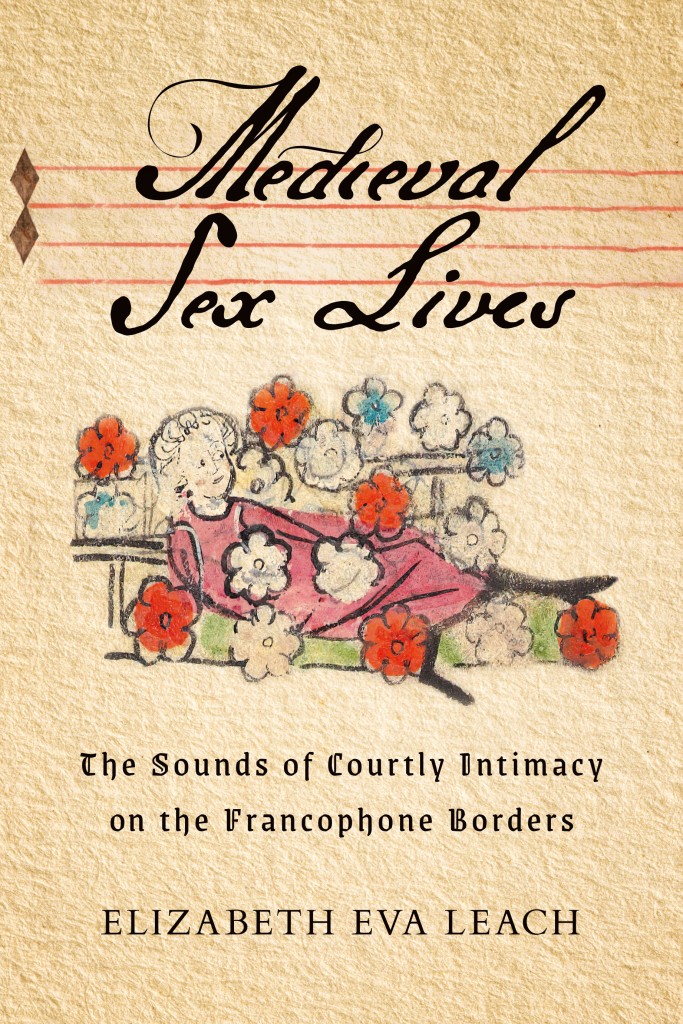

The publishers, Cornell University Press, have sent me some marketing materials for my new book, including a code for 30% discount on orders (scroll down to the end of the post). This post just gives a summary, the cover image, and a few sections from the author questionnaire they sent, which should give a flavour of what’s in the book.

Summary

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Douce 308 preserves and re-copies the lyrics of over 500 songs, ranging from those written in the late twelfth century, to those composed only a few years before the manuscript was copied in the early fourteenth. Its lack of both musical notation and authorial attribution make it relatively unusual among Old French songbooks. Its arrangement by genre instead invites an investigation of the relationship between a long tradition of sung courtly lyric and the real lives of the people who enjoyed it, in particular their emotional, intimate, sexual lives, something for which little direct evidence exists.

Using the other main inclusion in the original plan for Douce 308, Jacques Bretel’s poetic account of a tournament, The Tournament at Chauvency, Medieval Sex Lives argues that song offered musical practices which provided fertile means of propagating and enabling various sexual scripts.

With a focus on parts of Douce 308 not yet treated in detail elsewhere, Medieval Sex Lives offers an account of the manuscript’s contents, its importance, and likely social milieu, with ample musical and poetic analysis. In the process it offers new ways of understanding Marian songs and sottes chansons, as well as arguing for a broadening of our understanding of the medieval pastourelle, both as a genre and as an imaginative prop. Ultimately, Medieval Sex Lives presents a provocative speculative hypothesis about courtly song in the early fourteenth century as a social force, focusing on its ability to model, instill, inspire, and support sexual behaviours, real and imaginary.

Three ideas in the book

- The idea that medieval people consumed cultural products (in this case, songs) that fed and moulded their sexual imaginations;

- The idea that an unnotated songbook might be very noisy with the sounds of sex and tournaments;

- The idea that minority sexual practices (queer sexualities and paraphilias of various kinds) were present in the distant past.

What inspired me to write the book?

This book arose from two different but related questions. First, I wondered why the sung lyric tradition of Western Europe that is generally called “courtly love had such a long and successful history. Second, I wanted to know why the unnotated songbook, Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Douce had bothered to preserve and re-copy the lyrics of over 500 such songs, ranging from those written in the late twelfth century, to those composed only a few years before the manuscript was copied in the early fourteenth. The lack of musical notation, which was never planned for its songs, makes this manuscriptunusual among Old French songbooks. Nonetheless, curating nearly 150 years of this long-lived tradition was clearly important to the patrons, compilers, owners, and users of this manuscript: but why?

How will this book make a difference in my field of study? In what way is my argument a controversial or one that will shake up preconceived ideas?

Overall, the book challenges the idea that medieval song has nothing (or little) to do with the real lives of its audiences. Ch2’s proposal of love songs as sexual scripts is a controversial use of sociological theory to treat medieval literature. In Ch3 it offers a new way of approaching the sotte chanson (‘silly song’) as something not merely humorous or satirical, but as a potentially serious erotic possibility. Ch4 treats The Tournament at Chauvency from the perspective of sound studies. And Ch5 offers a controversial reading of the medieval pastourelle that firstly expands the definition of the genre to include songs rarely considered as pastourelles (but collected by Douce 308 as such), and secondly makes a difficult argument about some of them as offering fantasies of sexual domination and rape that might have appealed (and been useful) to some audience members, specifically women and queer people.

Residents outside North America should use 30% Discount Code: FFF23 and order online at combinedacademic.co.uk. Details on this PDF: