A paper showing that the music’s functional, contrapuntal aspect can significantly inflect the meaning of the texts that it delivers.

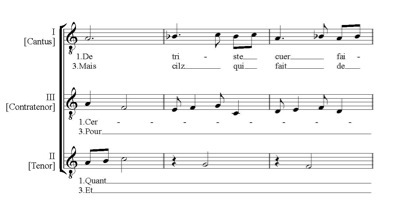

This article argues that our modern experience of songs and singing, whether expert, amateur, or entirely uninformed and passive, is almost completely misleading when it comes to appreciating the singing of late-medieval lyric. The focus here is on polyphonic songs that align several texts for simultaneous delivery—a somewhat special category of work. Machaut wrote three such works: Sans cuer/Amis/Dame (B17), Quant Theseus/Ne quier (B34) and De triste cuer/Quant/Certes (B29). I consider the first two of these briefly before focusing on the last one, B29, to show that the argument that the three differently texted voices present is significantly inflected by the musical (specifically the functional, contrapuntal) relationship between the voices that carry them.

Abstract

Music’s centrality to the construction of meaning in the texts of B29 and the other polytextual pieces reflects the broader cultural use of music as a meaningful—and not just a pleasant—component of lyric performance. I aim to bring out the potential significance of the dimension of performance—specifically sung musical performance—to scholars who normally consider only written forms of such works, whether poetic or musical. This article thus addresses both those literary scholars who might want to know what kinds of meanings a musical setting might add to a written poem that they usually consider just as verbal text (written or spoken) and those musicologists who might want to consider the performed moment of a piece in conjunction with their more usual “reading” of it as a notated modern score.

Link to the full-text PDF. Published as Elizabeth Eva Leach, “Music and Verbal Meaning: Machaut’s Polytextual Songs,” Speculum 85/3 (2010), 567-591. © Cambridge University Press 2010. Reprinted with permission.

Previously, the online subscription version (was available via CUP) and was accompanied by sound files that enable the listener to hear the individual voice parts, any two in combination, and the complete three-part balade. HOWEVER — since Speculum moved publisher, this is no long accessible, so I paste the raw mp3 files below.

Bibliography (some links require a subscription)

- Apel, Willi, ed. French Secular Compositions of the Fourteenth Century. 3 vols. Vol. 53, Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae. Rome: American Institute of Musicology, 1970-72.

- Bent, Margaret. “Deception, Exegesis and Sounding Number in Machaut’s Motet 15.” Early Music History 10 (1991): 15-27. [LINK via JSTOR]

- ———. “Naming of Parts: Notes on the Contratenor, c. 1350-1450.” In “Uno gentile et subtile ingenio”: Studies in Renaissance Music in Honour of Bonnie J. Blackburn, edited by Gioia Filocamo and M. Jennifer Bloxam, 1-12. Turnhout: Brepols, 2009.

- ———. “The Grammar of Early Music: Preconditions for Analysis.” In Tonal Structures in Early Music, edited by Cristle Collins Judd, 15-59. New York and London: Garland, 1998.

- Binski, Paul. Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation. London: The British Museum Press, 1996.

- Boogaart, Jacques. “‘O Series Summe Rata:’ De Motetten van Guillaume de Machaut. De Ordening van het Corpus en de Samenhang van Tekst en Muziek.” Utrecht, 2001.

- Boulton, Maureen Barry McCann. The Song in the Story: Lyric Insertions in French Narrative Fiction, 1200-1400. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.

- Brown, Thomas. “Another Mirror of Lovers? Order, Structure and Allusion in Machaut’s Motets.” Plainsong and Medieval Music 10 (2001): 121-34.

- Brownlee, Kevin. “Fire, Desire, Duration, Death: Machaut’s Motet 10.” In Citation and Authority in Medieval and Renaissance Musical Culture: Learning from the Learned, edited by Suzannah Clark and Elizabeth Eva Leach, 79–93. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2005.

- ———. “La polyphonie textuelle dans le Motet 7 de Machaut: Narcisse, la Rose, et la voix féminine.” In Guillaume de Machaut: 1300-2000, edited by Jacqueline Cerquiglini-Toulet and Nigel Wilkins, 137-46. Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 2002.

- ———. “Machaut’s Motet 15 and the Roman de la Rose: The Literary Context of Amours qui a le pouoir/Faus samblant m’a deceü/Vidi Dominum.” Early Music History 10 (1991): 1-14. [Link via JSTOR]

- ———. “Polyphonie et intertextualité dans les motets 8 et 4 de Guillaume de Machaut.” In “L’hostellerie de pensée”: Études sur l’art littéraire au Moyen Age offertes à Daniel Poirion, edited by Michel Zink, Danielle Bohler, Eric Hicks and Manuela Python, translated by Anthony Allen, 97-104. Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 1995.

- Busse Berger, Anna Maria. Medieval Music and the Art of Memory. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Butterfield, Ardis. “Enté: A Survey and Re-Assessment of the Term in Thirteenth and Fourteenth-Century Music and Poetry.” Early Music History 22 (2003): 67-101. [Link via JSTOR]

- ———. “Lyric and Elegy in The Book of the Duchess.” Medium Aevum 60, no. 1 (1991): 33-60.

- ———. Poetry and Music in Medieval France: From Jean Renart to Guillaume de Machaut. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Cerquiglini, Jacqueline. “Le nouveau lyricisme (XIVe-XVe siècle).” In Précis de littérature française du Moyen Âge, edited by Daniel Poirion, 275-92. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1983.

- Clark, Suzannah. “‘S’en dirai chançonete’: Hearing Text and Music in a Medieval Motet.” Plainsong and Medieval Music 16, no. 1 (2007): 31-59.

- Earp, Lawrence. Guillaume de Machaut: A Guide to Research. New York: Garland, 1995.

- Everist, Mark. “Motets, French Tenors and the Polyphonic Chanson ca .1300.” Journal of Musicology 24 (2007): 365-406.

- Gaunt, Simon. Gender and Genre in Medieval French Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Goehr, Lydia. The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

- Greene, Gordon K., ed. French Secular Music: Manuscript Chantilly, Musée Condé 564. Vols. 18-19, Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century. Monaco: L’oiseau-lyre, 1982.

- ———, ed. French Secular Music: Ballades and Canons. Vol. 20, Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century. Monaco: L’oiseau-lyre, 1982.

- Hoekstra, Gerald R. “The French Motet as Trope: Multiple Levels of Meaning in Quant florist la violete / El mois de mai / Et Gaudebit.” Speculum 73, no. 1 (1998): 32-57.

- Hoepffner, Ernest. Oeuvres de Guillaume de Machaut. 3 vols. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1908-1922.

- Holsinger, Bruce W. Music, Body, and Desire in Medieval Culture: Hildegard of Bingen to Chaucer. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001.

- Huot, Sylvia. Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet: The Sacred and Profane in Thirteenth-Century Polyphony. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

- ———. From Song to Book: The Poetics of Writing in Old French Lyric and Lyrical Narrative Poetry. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987.

- Kay, Sarah. “Touching Singularity: Consolation, Philosophy, and Poetry in the French dit.” In The Erotics of Consolation: Desire and Distance in the Late Middle Ages, edited by Catherine E. Léglu and Stephen J. Milner, 21-38. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Kelly, Douglas. Medieval Imagination: Rhetoric and the Poetry of Courtly Love. Madison, 1978.

- Kenny, Anthony, and Jan Pinborg. “Medieval Philosophical Literature.” In The Cambridge History of Later Medieval Philosophy: From the Rediscovery of Aristotle to the Disintegration of Scholasticism 1100-1600, edited by Norman Kretzmann, Anthony Kenny and Jan Pinborg, 11-42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Leach, Elizabeth Eva. “Counterpoint and Analysis in Fourteenth-Century Song.” Journal of Music Theory 44, no. 1 (2000): 45-79. [Link via JSTOR]

- ———. “Counterpoint as an Interpretative Tool: the Case of Guillaume de Machaut’s De toutes flours (B31).” Music Analysis 19, no. 3 (2000): 321-51. [Link via JSTOR]

- ———. Guillaume de Machaut: Secretary, Poet, Musician. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011.

- ———. “Love, Hope, and the Nature of Merci in Machaut’s Musical Balades Esperance (B13) and Je ne cuit pas (B14).” French Forum 28, no. 1 (2003): 1-27.

- ———. “Machaut’s Balades with Four Voices.” Plainsong and Medieval Music 10, no. 2 (2001): 47-79.

- ———. “Machaut’s Peer, Thomas Paien.” Plainsong and Medieval Music 18, no. 2 (2009): 1-22.

- ———. “Nature’s Forge and Mechanical Production: Writing, Reading, and Performing Song.” In Rhetoric beyond Words: Delight and Persuasion in the Arts of the Middle Ages, edited by Mary Carruthers, 72-95. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- ———. Sung Birds: Music, Nature, and Poetry in the Later Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007.

- Leech-Wilkinson, Daniel, and R. Barton Palmer, eds. Guillaume de Machaut: Le livre dou voir dit (The Book of the True Poem). Vol. 106, Garland Library of Medieval Literature. New York: Garland, 1998.

- Leupin, Alexandre. “The Powerlessness of Writing: Guillaume de Machaut, the Gorgon and Ordenance.” Yale French Studies 70, no. Images of Power: Medieval History/Discourse/Literature (1986): 127-49. [Link via JSTOR]

- Ludwig, Friedrich, ed. Guillaume de Machaut: Musikalische Werke, Publikationen älterer Musik. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1926-1954.

- Marenbon, John. Later Medieval Philosophy (1150-1350): An Introduction. London: Routledge, 1987.

- McGrady, Deborah. Controlling Readers: Guillaume de Machaut and His Late Medieval Audience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

- Newes, Virginia. “Amorous Dialogues: Poetic Topos and Polyphonic Texture in Some Polytextual Songs of the Late Middle Ages.” In Critica Musica: Essays in Honor of Paul Brainard, edited by John Knowles, 279-306. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach, 1996.

- ———. “The Bitextual Ballade from the Manuscript Torino J.II.9 and its Models.” In The Cypriot Repertory of the Manuscript Torino J.II.9, edited by Ursula Günther and Ludwig Finscher, Vol. 45, 491-519. [np]: American Institute of Musicology, 1995.

- Page, Christopher. “Around the Performance of a Thirteenth-Century Motet.” Early Music 28 (2000): 343-57.

- ———. Discarding Images: Reflections on Music and Culture in Medieval France. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- ———. “Johannes Grocheio on Secular Music: A Corrected Text and a New Translation.” Plainsong and Medieval Music 2 (1993): 17-41.

- Perkinson, Stephen. “Portraits and Counterfeits: Villard de Honnecourt and Thirteenth-Century Theories of Representation.” In Excavating the Medieval Image: Manuscripts, Artists, Audiences: Essays in Honor of Sandra Hindman, edited by Nina A. Rowe and David S. Areford, 13-36. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

- Robertson, Anne Walters. Guillaume de Machaut and Reims: Context and Meaning in His Musical Works. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Schoen-Nazzaro, Mary B. “Plato and Aristotle on the Ends of Music.” Laval théologique et philosophique 34, no. 3 (1978): 261-73.

- Schrade, Leo, ed. The Works of Guillaume de Machaut. 2 vols, Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century. Les Remparts, Monaco: L’Oiseau-Lyre, 1956.

- Sears, Elizabeth. “Sensory Perception and its Metaphors in the Time of Richard of Fournival.” In Medicine and the Five Senses, edited by W. F. Bynum and R. Porter, 17-39. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Talbot, Michael, ed. The Musical Work: Reality or Invention? Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000.

- Wimsatt, James I., William W. Kibler, and Rebecca A. Baltzer, eds. Guillaume de Machaut: Le Jugement du Roy de Behaigne and Remede de Fortune. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1988.

- Zeeman, Nicolette. “The Lover-Poet and Love as the Most Pleasing ‘Matere’ in Medieval French Love Poetry.” Modern Language Review 83, no. 4 (1988): 820-42. [Access via JSTOR]